Two sides of modern warfare sit in stark contrast

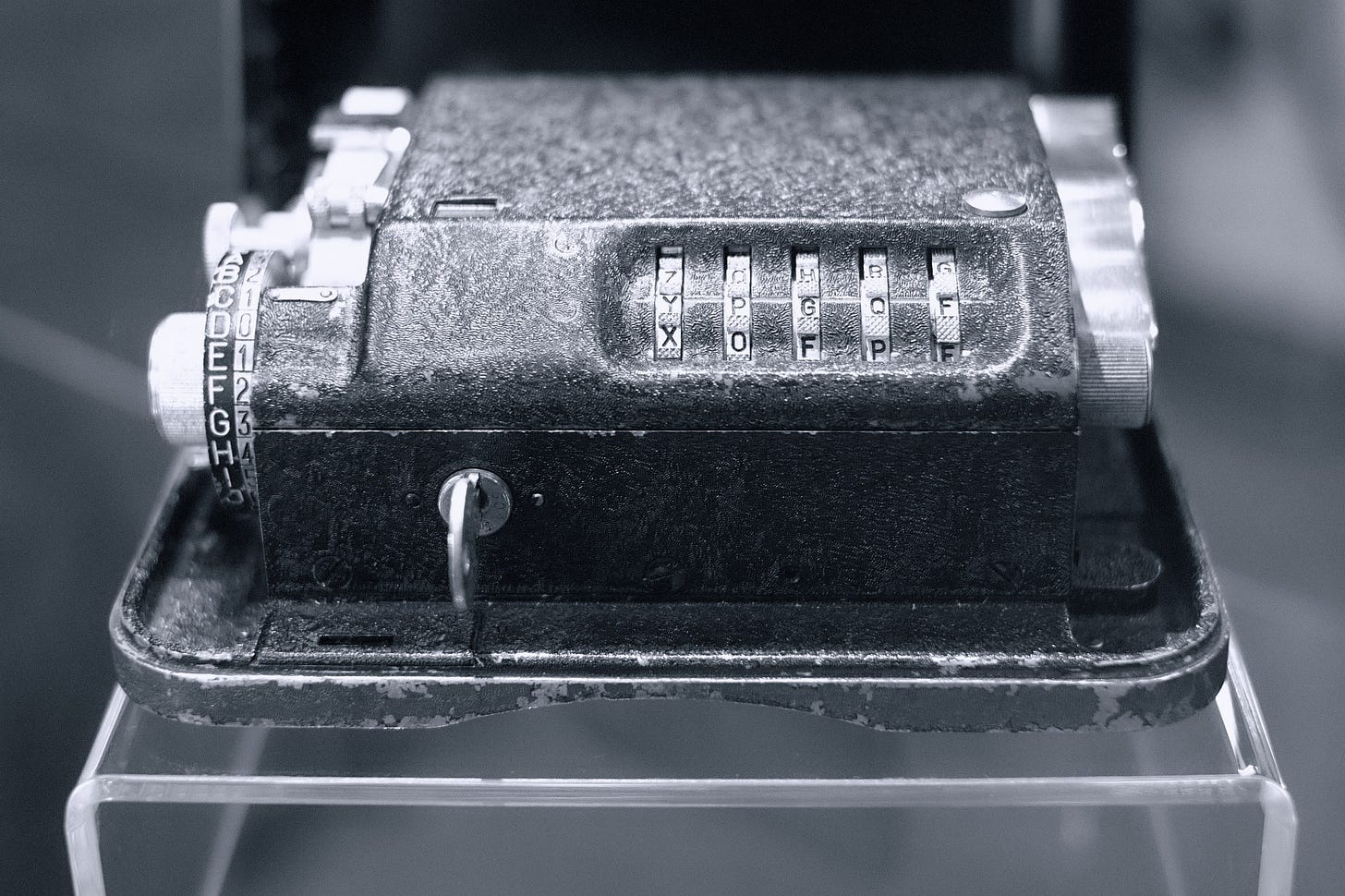

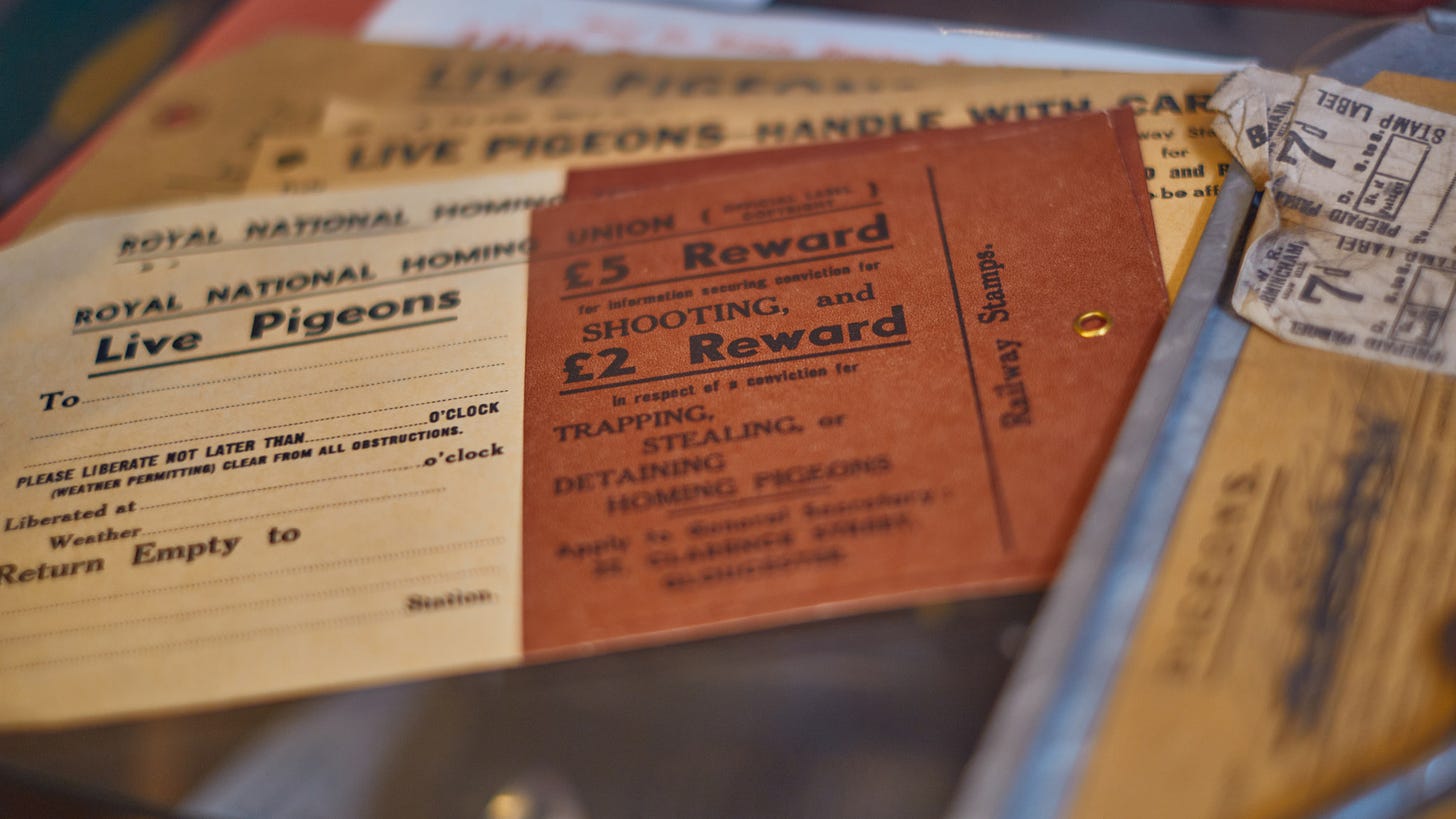

Yesterday was a significant day for me. I finally got to visit Bletchley Park, home of the WW2 codebreakers who helped the Allies to defeat the Nazis. It has been an intention and ambition of mine for some time to make the pilgrimage to this site, as it has relevance to me personally at multiple levels. Walking around provoked some thoughts about the nature of information warfare past and present that I felt were worth sharing. In particular, I could see the opposing paradigms of the past and present.

Bletchley Park is not only the place where the German’s Enigma codes were broken, it is also one of the homes of modern computer science through its association with Alan Turing. I read Mathematics and Computation at university, and studied the theory of computability as well as formal methods of proof of software correctness. These trace back to the work of Turing and other pioneers of the 1930s and 1940s. They put in place the foundations for what it means “to compute”, and what a successful computational outcome might be.

I had a fairly conventional career in IT before moving to telecoms in the early 2000s. My curiosity led me to search for the fundamental theoretical foundations of my newly adopted industry. The harder I looked, the stranger it became: they seemed to exist in basic data transmission in terms of the physics, but were absent when it came to the distribution of computation via packet data. In time I located the innovators who had solved (independently) the critical missing pieces of what it means to “translocate” (i.e. copy at a distance) information.

The theory of computability largely preceded the development of the modern digital computers. Industrialisation of “classical” computing happened on solid theoretical foundations. (I have nothing to say on quantum computing — not my subject area.) In contrast, the current Internet is a collection of hacks that lack a solid science and engineering basis. That is why we have to endure reliability, security, and flexibility constraints that we would not tolerate in any other kind of technological system. We treat the “circle of death” of buffering video as being normal, when it is not.

The idea that simple facts have been overlooked — two repeating layers at different scopes, two degrees of freedom, no quality in averages, embedding of a false “work” metaphor, the need for encapsulation — is unthinkable to those who have been given certificates and awards in packet network engineering. The economic and cultural success of the current Internet is mistaken for it being the pinnacle of all possible internets that we could construct, when it is nothing of the kind. By building practical examples that exceed it, the value of fixing the underlying theoretical foundations could be demonstrated.

The work I was involved in, more in a role of impresario than inventor, was to augment the Church/Turing/Von Neumann idea of “computability” with a complementary idea of “information translocatability”. It turns out that the essential simplicity has been missed, making modern networks unnecessarily complex, brittle, and unreliable. Over time it became apparent that the challenge was not articulating these principles, but rather overcoming the psychological, cultural, and social barriers to them being heard and adopted.

Because my various associates could build “impossible” things (according to the incumbent limiting paradigm), we could be certain that we were not crazy, just under-appreciated. It gave me a confidence in going up against orthodoxy while being ignored or ridiculed, a skill that would soon become critical when applied to geopolitics. The cryptographic world of Turing was all about keeping secrets and outwitting others via pure intellect. While I was genuinely working on a unified theory of distributed computation, the focus was different. My telecoms work was about making everyone aware of truth that was previously not perceived.

The skill I acquired as a result was mapping people’s current (mis)understanding in a learning journey, and helping them to locate themselves on that path, so they could take the next step on their own timing. Simply ramming “helpful technical reality” down their throats got us nowhere. The ability to empathise with their limits of thinking, and engage with their constraining pride, was more important than proving that you could out-think or intellectually dominate them. It gave me a “bridge” experience between the mind-led academic world of computer programming (exemplified by Bletchley’s codebreakers) and the heart-led human deprogramming of Q.

Those involved in WW2 clearly knew they were at war. The current unrestricted fifth-generation war we are embroiled in is the exact opposite: most people are unaware that they have been subjected to the most intense psychological attack. Being at Bletchley yesterday was somewhat bizarre for me, since I know I am active at the battlefront, yet surrounded by people who have no idea that we are de facto in WW3. I was asked by a guide whether my interest in Bletchley was principally historic or technical, and I could not help but chuckle aloud, unable to pick either. All I could say was that I had an intense personal connection to the subject matter.

The task of the 2020s is in many ways the exact opposite of the 1940s. We are called to de-occultise society, taking what was previously hidden and make it widely available and understood in the open. The challenge is not intellectual in nature, but rather more driven by staying loving and connected with our fellow (brainwashed and scared) human beings. In many ways the computers have become our enemies rather than helpers, with hidden AI being used to imperceptibly socially engineer society and the beliefs of the masses. The visible heroics are done by isolated individuals waking up and joining up as a civilian peace corps, rather than formal organised military (who no doubt take on a vast burden yet to be seen or appreciated).

It is beyond the comprehension of most that WW2 was not what it seemed to be, and that the Nazis did not really lose (even if the German people certainly did). They regrouped in the Americas and Antarctica, and switched from invasion to infiltration. The same bankers were backing both sides, and WW2 never really ended. I recall watching endless WW2 films on afternoon TV as a child, and can now see them for the propaganda they really are. It is hard to go to any museum these days and take what is presented as literal fact. There are always some lies mixed in with truth. It is painful to realise that we have been deceived and deluded.

I wonder what Turing would have made of the meme makers and digital warriors of the 21st century, also fighting an information war, but of a very different kind. I have one foot in both worlds, being both a computer scientist, active at the forefront of knowledge, as well as being a activist helping ordinary people to see through the web of lies we have been indoctrinated with. The problem then was keeping secrets, rather than eliminating them. The critical skill then was detailed analysis, rather than “join the dots” synthesis. The constraining limit then was raw intellect, rather than empathy with the audience.

As a final departing thought, there was one part of yesterday’s experience that could easily be ignored or overlooked. Outside Bletchley train station there was a union picket line against the removal of guards and station staff. A tourist attraction like Bletchley Park now has a station where nobody can take your cash, help the disabled, or meet and greet foreign visitors who may need assistance. We do not value jobs which have social benefit, and employ those with a human touch, but cannot generate monetary returns. So much effort has been invested into warfare, yet we seem to lack peace as a people.

Perhaps the sign we have truly won this war is that all these people have a future free from material want or lack of purpose. Bletchley town itself seems rather impoverished. I guess someday there will be museums to the Great Awakening and the role of anons, too. Let’s hope that they have happier surroundings without the social conflict, economic insecurity, pharma genocide, treacherous leaders, and media brainwashing.

Read It Now

Read It Now